- Other Old English Texts Iirejected Scriptures Pdf

- Other Old English Texts Iirejected Scriptures Verses

- Other Old English Texts Iirejected Scriptures Reading

- Other Old English Texts Iirejected Scriptures Study

The Bible is an ancient text. Like every other ancient text, the originals have not survived the ravages of time. What we have are copies of the original which date to hundreds of years after their composition. This is normal for ancient texts. For example, Julius Caesar chronicled his conquest of Gaul in his work On The Gallic War in the first century B.C. The earliest manuscript in existence dates to the 8th century AD, some 900 years later.1 So what are the oldest biblical texts discovered to date?

Other Old English Texts Iirejected Scriptures Pdf

Anglo-Saxon translators produced several Old English translations and glosses of individual books of the Latin Bible. More information. The Paris Psalter, and related texts. Cain's Face, and Other Problems: The Legacy of the Earliest English Bible Translations. And Other Problems: The Legacy of the Earliest English Bible Translations. Other Old English Texts I Other Old English Texts II Other Old English Texts III THE BOOK OF THE TWO PEARLS NEW APOCRYPHAL COLLECTIONS THE TREATISE OF SHEM - A NEW TRANSLATION THE APOCALYPSE OF THE HOLY MOTHER OF GOD CONCERNING THE CHASTISEMENTS The Fragments of. The World English Bible (WEB) is a Public Domain (no copyright) Modern English translation of the Holy Bible, based on the American Standard Version of the Holy Bible first published in 1901, the Biblia Hebraica Stutgartensa Old Testament, and the Greek Majority Text New Testament.

The Nash Papyrus

The Nash Papyrus is a manuscript that was purchased in Egypt in 1902 from an antiquities dealer by Walter Llewellyn Nash. Written in Hebrew and dating to the second century B.C. it was the oldest known biblical text prior to the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls.2 It contains the 10 commandments from the book of Exodus, and the Shema Yisrael prayer (“Hear, O Israel: the LORD God, the LORD is one”) from Deuteronomy. Ancient Jewish sources state that it was common practice to read the Ten Commandments before saying the Shema prayer.3 Some scholars believe the Nash Papyrus was used by an Egyptian Jew in his daily worship.

The Dead Sea Scrolls

The Dead Sea Scrolls are a collection of over 900 manuscripts discovered in the caves around Qumran near the Dead Sea. Between in 1947 and 1956 numerous excavations discovered a variety of scrolls and fragments in 11 caves, including copies of every book of the Old Testament except for Nehemiah and Esther.4 The manuscripts date from the third century B.C. to the first century A.D., with some of the earliest, such as 4Q17 (4QExod-Levf), dating to the early Hellenistic era, approximately 250 B.C.5 Before their discovery, the earliest complete Old Testament manuscript was the Leningrad Codex, dating to A.D. 1008. The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls allowed scholars to see how much the biblical text had changed in over 1000 years of transmission. They discovered that very little had changed and that the Hebrew Bible had been transmitted with incredible accuracy over a millennium.

The Silver Ketef Hinnom Scrolls

The oldest biblical text is on the Hinnom Scrolls – two silver amulets that date to the seventh century B.C. These rolled-up pieces of silver were discovered in 1979-80, during excavations led by Gabriel Barklay in a series of burial caves at Ketef Hinnom. When the silver scrolls were unrolled and translated, they revealed the priestly Benediction from Num 6:24-26 reading, “May Yahweh bless you and keep you; May Yahweh cause his face to Shine upon you and grant you Peace.”6 The Ketef Hinnom scrolls contain the oldest portion of Scripture ever found outside of the Bible and significantly predate even the earliest Dead Sea Scrolls. They also contain the oldest extra-biblical reference to YHWH. Given their early date, they provide evidence that the books of Moses were not written in the exilic or postexilic period as some critics have suggested.

There are other ancient texts which allude to the Bible. The 10th-century B.C. Khirbet Qeiyafa ostracon is similar to such Scriptures as Exodus 23:2, Psalm 72:4 and Isaiah 1:17.7 The Elephantine “Passover” Papyrus, dating to 419 B.C. almost certainly references the instructions for keeping the Feast of Unleavened Bread found in Ex. 12:15.8 However, I’ve chosen to narrow the focus of my list to include only the oldest ones that contain clear sections of Scripture from the Hebrew Old Testament.

With the number of archaeological excavations under way throughout the Middle East, it is only a matter of time until we see more ancient biblical texts uncovered. Given the recent search for more Dead Sea Scroll caves,9 this may be sooner rather than later.

Endnotes

1 McDowell, Josh, and Sean McDowell. Evidence That Demands a Verdict: Life-Changing Truth for a Skeptical World. Authentic, 2017. Pg. 59.

Other Old English Texts Iirejected Scriptures Verses

2 https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-OR-00233/1 (Accessed January 24, 2019)

3 https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-OR-00233/1 (Accessed January 24, 2019)

4 http://dss.collections.imj.org.il/significance (Accessed January 24, 2019)

5 https://www.deadseascrolls.org.il/explore-the-archive/manuscript/4Q17-1 (Accessed January 24, 2019)

6 http://www.biblearchaeology.org/post/2010/01/06/The-Blessing-of-the-Silver-Scrolls.aspx (Accessed January 24, 2019)

7 http://www.biblearchaeology.org/post/2010/01/10/Ancient-Hebrew-Inscription-Dated-to-time-of-David.aspx (Accessed January 24, 2019)

8 http://cojs.org/the_passover_papyrus_from_elephantine-_419_bce/ (Accessed January 24, 2019)

9 https://www.timesofisrael.com/newly-discovered-caves-may-hold-more-dead-sea-scrolls/ (Accessed January 24, 2019)

| The Bible in English |

|---|

| Bible portal |

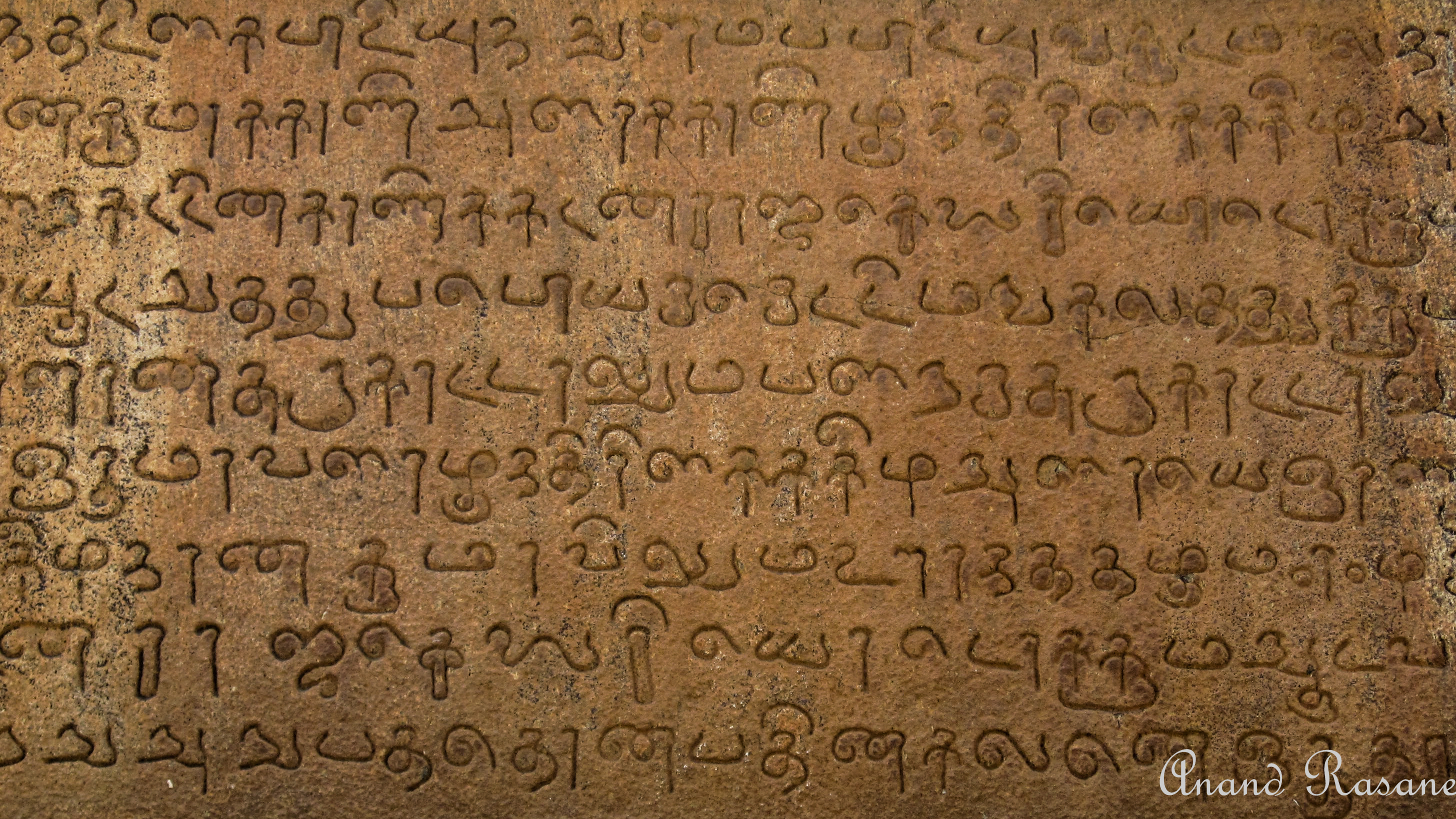

The Old English Bible translations are the partial translations of the Bible prepared in medieval England into the Old English language. The translations are from Latin texts, not the original languages.

Many of these translations were in fact Bible glosses, prepared to assist clerics whose grasp of Latin was imperfect and circulated in connection with the Vulgate Latin Bible that was standard in Western Christianity at the time. Old English was one of very few early medieval vernacular languages the Bible was translated into,[1] and featured a number of incomplete Bible translations, some of which were meant to be circulated, like the Paris Psalter[2] or Ælfric's Hexateuch.[3]

Early history (600-874)[edit]

Information about translations is limited before the Synod of Whitby in 664. Aldhelm, Bishop of Sherborne and Abbot of Malmesbury (639–709), is thought to have written an Old English translation of the Psalms, although this is disputed.[according to whom?]

Cædmon (~657–684) is mentioned by Bede as one who sang poems in Old English based on the Bible stories, but he was not involved in translation per se.

Bede (c. 672–735) produced a translation of the Gospel of John into Old English, which he is said to have prepared shortly before his death. This translation is lost; we know of its existence from Cuthbert of Jarrow's account of Bede's death.[4]

The Vespasian Psalter[5] (~850–875) is an interlinear gloss of the Book of Psalms in the Mercian dialect.[6] Eleven other Anglo-Saxon (and two later) psalters with Old English glosses are known.[7][8] The earliest are probably the early-9th-century red glosses of the Blickling Psalter (Pierpont Morgan Library, M.776).[9][10] The latest Old English gloss is contained in the 12th-century Eadwine Psalter.[11] The Old English material in the Tiberius Psalter of around 1050 includes a continuous interlinear gloss of the psalms.

Alfred and the House of Wessex (875-999)[edit]

As England was consolidated under the House of Wessex, led by descendants of Alfred the Great and Edward the Elder, translations continued. King Alfred (849–899) circulated a number of passages of the Bible in the vernacular. These included passages from the Ten Commandments and the Pentateuch, which he prefixed to a code of laws he promulgated around this time. Alfred is also said to have directed the Book of Psalms to have been translated into Old English, though scholars are divided on Alfredian authorship of the Paris Psalter collection of the first fifty Psalms.[12][13]

Between 950 and 970, Aldred the Scribe added a gloss in the Northumbrian dialect of Old English (the Northumbrian Gloss on the Gospels) to the Lindisfarne Gospels as well as a foreword describing who wrote and decorated it. Its version of The Lord's Prayer is as follows:

- Suae ðonne iuih gie bidde fader urer ðu arð ðu bist in heofnum & in heofnas; sie gehalgad noma ðin; to-cymeð ric ðin. sie willo ðin suae is in heofne & in eorðo. hlaf userne oferwistlic sel us to dæg. & forgef us scylda usra suae uoe forgefon scyldgum usum. & ne inlæd usih in costunge ah gefrig usich from yfle

Other Old English Texts Iirejected Scriptures Reading

At around the same time (~950–970), a priest named Farman wrote a gloss on the Gospel of Matthew that is preserved in a manuscript called the Rushworth Gospels.[14]

In approximately 990, a full and freestanding version of the four Gospels in idiomatic Old English appeared in the West Saxon dialect and are known as the Wessex Gospels. Seven manuscript copies of this translation have survived. This translation gives us the most familiar Old English version of Matthew 6:9–13, the Lord's Prayer:

- Fæder ure þu þe eart on heofonum, si þin nama gehalgod. To becume þin rice, gewurþe ðin willa, on eorðan swa swa on heofonum. Urne gedæghwamlican hlaf syle us todæg, and forgyf us ure gyltas, swa swa we forgyfað urum gyltendum. And ne gelæd þu us on costnunge, ac alys us of yfele. Soþlice.

At about the same time as the Wessex Gospels (~990), the priest Ælfric of Eynsham produced an independent translation of the Pentateuch with books of Joshua and Judges. His translations were used for the illustrated Old English Hexateuch.

Late Anglo-Saxon translations (after 1000)[edit]

The Junius manuscript (initially ascribed to Cædmon) was copied about 1000. It includes Biblical material in vernacular verses: Genesis in two versions (Genesis A and Genesis B), Exodus, Daniel, and Christ and Satan, from the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus.

The three related manuscripts, Royal 1 A. xiv at the British Library, Bodley 441 and Hatton 38 at the Bodleian Library, are written in Old English, although produced in the late 12th century. Hatton 38 is noted as being written in the latest Kentish form of West Saxon.[15] They cover the four Gospels, with one section (Luke 16.14–17.1) missing from both manuscripts, Hatton and Royal.[16]

In 1066, the Norman Conquest of England marked the beginning of the end of the Old English language. Translating the Bible into Old English gradually ended with the movement from Old English to Middle English, and eventually there were attempts to provide Middle English Bible translations.

References[edit]

- ^Stanton 2002, p. 101: 'There was very little translation of the Bible into any Western vernacular in the Middle Ages, and as with other kinds of texts, English was precocious in this regard. The portions of the Bible translated into Old English are among the earliest vernacular versions of the Latin Bible in Western Europe'

- ^MS fonds latin 8824, not to be confused with the Byzantine Paris Psalter

- ^Stanton 2002, p. 126, 162.

- ^Dobbie 1937.

- ^Wright 1967.

- ^See also Roberts 2011, which looks at three Anglo-Saxon glossed psalters and how layers of gloss and text, language and layout, speak to the meditative reader.

- ^Roberts 2011, p. 74, n. 5

- ^Gretsch 2000, p. 85–87.

- ^Roberts 2011, p. 61.

- ^McGowan 2007, p. 205.

- ^Harsley 1889.

- ^Colgrave 1958.

- ^Treschow, Gill & Swartz 2012, §19ff

- ^Stevenson & Waring 1854–1865.

- ^MS. Hatton 38 2011, vol. 2, pt. 2, p. 837

- ^Kato 2013.

Other Old English Texts Iirejected Scriptures Study

Sources[edit]

- Colgrave, B., ed. (1958), The Paris Psalter: MS. Bibliothèque nationale fonds latin 8824, Early English Manuscripts in Facsimile, 8, Copenhagen: Rosenkilde and Bagger, OCLC717585.

- Dekker, Kees (2008), 'Reading the Anglo-Saxon Gospels in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries', in Hall, Thoman N.; Scragg, Donald (eds.), Anglo-Saxon Books and Their Readers, Kalamazoo, MI, pp. 68–93, ISBN978-1580441377.

- Dobbie, E. Van Kirk (1937), The Manuscripts of Caedmon's Hymn and Bede's Death Song with a Critical Text of the Epistola Cuthberti de obitu Bedae, New York: Columbia University Press, OCLC188505.

- Gretsch, Mechthild (2000), 'The Junius Psalter gloss: its historical and cultural context', Anglo-Saxon England, 29: 85–121, doi:10.1017/S0263675100002428.

- Harsley, F, ed. (1889), Eadwine's Canterbury Psalter, Early English Text Society, 92, London: Early English Text Society, OCLC360348.

- Kato, Takako (2013), 'Oxford, Bodley, Hatton 38: Gospels', in Da Rold, Orietta; Kato, Takako; Swan, Mary; Treharne, Elaine (eds.), The Production and Use of English Manuscripts 1060 to 1220, ISBN095323195X.

- McGowan, Joseph P. (2007), 'On the 'Red' Blickling Psalter Glosses', Notes and Queries, 54 (3): 205–207, doi:10.1093/notesj/gjm132.

- 'MSS. Hatton', Bodleian Library Catalog, University of Oxford, 8 July 2011, archived from the original on 27 January 2013

- Roberts, Jane (2011), 'Some Psalter Glosses in Their Immediate Context', in Silec, Tatjana; Chai-Elsholz, Raeleen; Carruthers, Leo (eds.), Palimpsests and the Literary Imagination of Medieval England: Collected Essays, pp. 61–79, ISBN9780230100268.

- Stanton, Robert (2002), The Culture of Translation in Anglo-Saxon England, Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, ISBN9780859916431.

- Stevenson, Joseph; Waring, George, eds. (1854–1865), The Lindisfarne and Rushworth Gospels, 28, 39, 43, 48, Durham: Surtees Society.

- Treschow, Michael; Gill, Paramjit; Swartz, Tim B. (2012), 'King Alfred's Scholarly Writings and the Authorship of the First Fifty Prose Psalms', The Heroic Age, 12

- Wright, David H., ed. (1967), The Vespasian Psalter, Early English Manuscripts in Facsimile, 14, Copenhagen: Rosenkilde and Bagger, OCLC5009657.

External links[edit]

- Ða Halgan Godspel on Englisc ('The Holy Gospels in English'), mostly based on Cod. Bibl. Pub. Cant. Ii. 2. 11.

- Anglo-Saxon Versions of Scripture (some information)

- Translators and Translations of the Anglo Saxon Bible by Ian Williams, 2000.